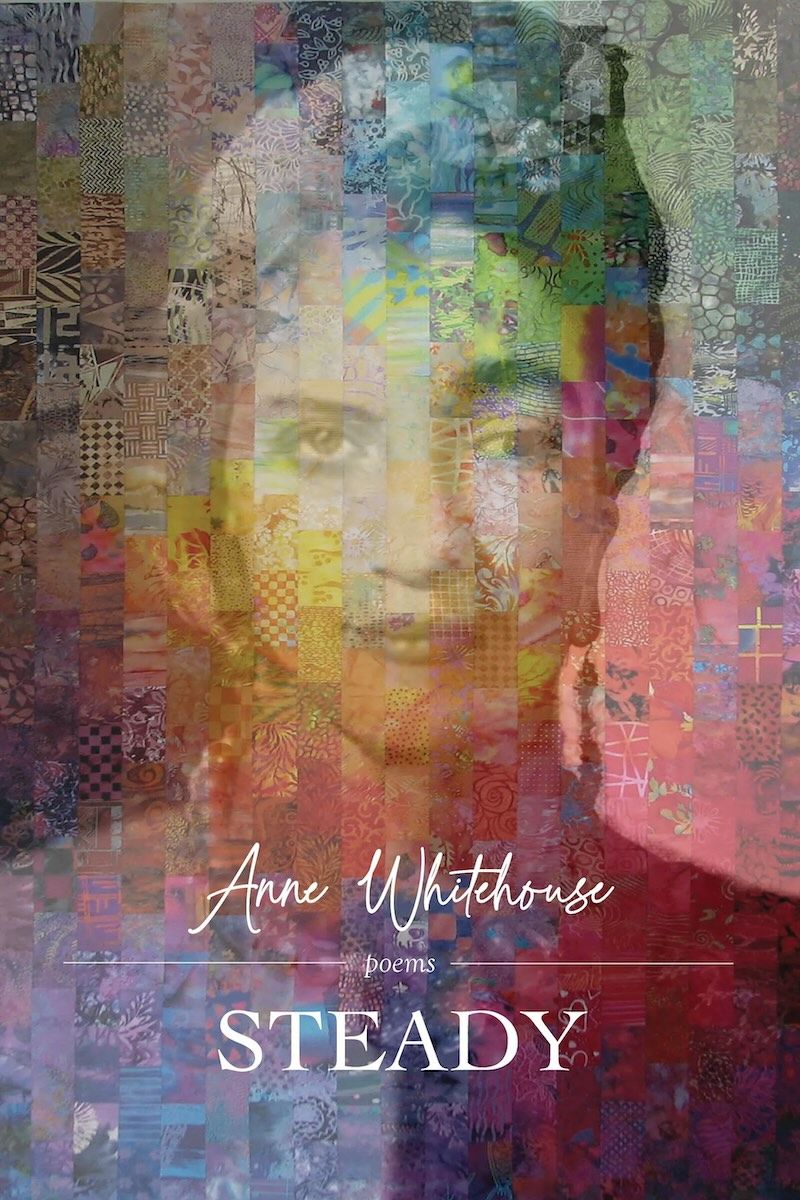

Poetry Review: Steady by Anne Whitehouse

Anne Whitehouse's poetry collection, Steady, isn't a poetry collection. Rather, it isn't just a poetry collection. I, perhaps naively, set about reading it without first getting a sense of its length or breadth.

The book is divided into four Parts. The first, second and fourth sections, titled Morning Swim, Signs, and Blue respectively, each contain exactly 10 poems. I didn't notice that at first, but later, when I was done and considering how everything fit together, I wasn't surprised to see the uniformity of this. I'm sure it's not coincidence, even if I don't grok the significance of the number 10, because every piece in every section seems meticulously calculated.

To what end? I'm honestly not certain. But something happened to me through the reading. At one point, while reading Part III - An Art Story, I found myself asking, "What is she doing to me?"

I'm hoping a second reading will help me recognize more clearly the ways in which I was transformed by this incantatory book. So, this is more of an exploration than a review.

Part I - Morning Swim opens with a cinematic tableaux of nature that reminded me of Terence Malick.

The island sparkles in the morning.

Grasses nodding, leaves waving,

All alive and moving, yet still rooted.

The day passes in sunlight and shadow.

Billowy clouds blow across the sun.

What seems like silence

is full of sound.

Rocked by gentle waves,

And dark blue sea,

Bathed in endless waters

That are cold, healing, and bitter.

A vast expanse awaits. From a distance, all is calm and serene. But like that "silence… full of sound," something looms. It's only in the final line that a body touches water and it hits like that first jarring shock of cold against the skin when jumping in.

The next few poems cycle through all the seasons as we are slowly introduced to the life of the poet through memories of friends and family, most of whom we meet without introduction or explanation. The second poem, Snowdrops, is a memorial, meaning we didn't have to wait long for the promise of the first poem to be revealed in the ghost of a lost friend, Paul.

In Pond Lives the poet has already become 'we' without elaboration. Presumably, this is a significant other, a partner or spouse, but we are left to wonder. 'Lives' in the title can be read two ways: as if the pond itself is living, or as a reference to the many lives of the creatures who populate the pond: fungi, bacteria, worms, fish, a turtle, snakes, and crabs. The pond is full of life but also of dead plants, detritus and decomposing matter.

Part I is as populated with human lives as the pond is with creatures. Morning Swim takes a deep dive into the poet's past where me meet Whitehouse's mother (now dead), sisters, daughter, a husband who may or may not be of the 'we' from earlier, and a host of other people, many of whom are women and artists, and at least one of whom may be a stand-in for Whitehouse.

Marie Kondo arrives like a fairy

from another realm…

She orders clients to bring all they have

out into the open and look at it,

touch it, and own it…

She teaches that there is joy in order

and order in joy.

In Yahrezeit, we learn that Whitehouse's parents are

by a quirk of the Hebrew calendar,

yoked forever and forever,

until the end of time

just as it seems the author herself is yoked forever to the many people we meet through this section. There's a kind of cacophony of people and relationships here that these poems are seeking to assemble into a manageable whole. Like Marie Kondo, Whitehouse appears to be clapping "her hands together at the sight of chaos."

Part II - Signs continues in this fashion through a later stage of the poet's life, after opening with something of an enigma. Signs reads a bit like a mystery, but if so, it may also hold within itself a key. After a spring snow threatens recently planted daffodils, hyacinths, and lettuces, we are reassured.

Perhaps patience is the key, I thought.

How hard it is to wait out a siege.

The enemy is the invisible virus,

and there is now way out but through.

Once it has passed, we will have to know

where to look to spot the absences

only glaring for those who miss

what has ceased to exist.

Isn't this what memory is after all, a recognition of what has passed and is now gone? All we have left is the looking.

During this section we meet many more characters, including two (three?) more possible husbands, and an assortment of awkward, eccentric, or downright bad men. The timeline has also broadened. Most of what transpired before seemed to have been in the poet's lifetime, but these poems are scattered through time from "1978," to "nearly a century ago," to "once upon a time," to "one hundred fifty years later."

The second poem in Part II, Lady Bird, opens with what might be a thesis for what follows.

In my day, women had their sphere,

and men had theirs.

The sphere of men is then revealed to be comprised of a disappointing husband, male professors behaving badly, Robert Frost nipping a tie, an old professor forgetting an appointment with the poet, and finally, the poet Mark Strand being too focused on a young male acolyte to notice the female author waiting for his signature.

Some of these tales are imbued with a respectful aura of nostalgia, despite the fact that they portray a misogynistic world of letters.

The penultimate poem in Part II signals a turning point. From the Life of Iris Origo (a cento, mostly) is part persona poem and part biographical narrative poem, about a writer whom I hadn't heard of before. (I'm not clear if the words of Origo in this poem are her own or Whitehouse's imagination, but it reads like a mix of both.)

Iris Origo's life as depicted here seems to summarize all of what has preceded it in this collection, and portend some of what is to follow. We also see a familiar refrain.

At seven, she lost

her beloved American father

who died of TB at thirty.

At seven, her only. son

succumbed to meningitis.

These losses defined her life

with the negative space

of their cancelled lives

and her unfulfilled longings.

Origo was raised and taught by men in the world of men, and she ultimately had to overcome and learn to disregard the "values I did not share," of that world. "Of life's pleasures," Whitehouse/Origo writes, "only books and reading, at every age, have never failed me."

Ultimately, Origo finds purpose and success in transforming herself from "being an observer to being observed, assemble the part's of someone else's life and character into a pattern."

Some of the poems in this collection read like invocations or alchemical prognostications. Poisons and Medicines, from Part I, opens with a quote by the Swiss physician, theologian and alchemist, Paracelsus.

All things are poisons, and nothing is without poison; only the dose makes a thing not a poison.

Whitehouse writes here about rituals, sorcery, and healing. This poem is a litany of plants, herbs and potions. It is only through study and sorting and classifying that we can survive the many biological agents and substances which are as likely to kill as they are to heal.

Dante's Tomb, which closes Part II, is another such incantation of a poem that reads like an ekphrastic fable. In it, we learn about The Palacio Barolo, a skyscraper-sized monument to Dante that was constructed in Argentina by the Italian architect, Mario Pilanti. The poem describes a magnificent structure of "twenty-two floors representing twenty-two stanzas, scaled to the golden ratio," and "crowned with Latin inscriptions and statues of serpents, dragons, and condors," with "geometric patterns representing alchemist's fire and Masonic symbols."

This fabulist poem spans hundreds of years and encompasses a mystery, which ends on a note that resonates with previously established imagery, which, if I were to name it here, would feel like a spoiler. It's a glorious ending to the first half of this collection.

I'm going to say little about Part III - An Art Story and the works that make up this section of this collection. Ironically (or not) it's the longest section of the four and takes up almost half of the pages in the volume.

An Art Story is a fascinating tale, subdivided into five parts. It tracks an artifact, a two-thousand year old mosaic, from its creation to a contemporary legal battle involving it. The story is told in a few different voices, some of which contradict each other. It almost reads like a mystery novel. I thoroughly enjoyed it, but it also threw me off balance (deliberately, I presume).

An Art Story is followed by six lengthy narrative poems about several artists, including Leonora Carrington, Lee Miller, Frida Kahlo, Ruth Asawa and Imogen Cunningham, and with appearances by many other well known artists. These women artists come off as heroic, and rightly so, while most of the men whose lives touched theirs were terrible. This is an observation, not a complaint.

Unfortunately, my understanding of these artists and their eras is limited, and after reading this section, it remains so. It was around this time I found myself asking, "What is Whitehouse doing to me?"

These pieces are so full of information, people, interaction. anecdotes, and biography, that I felt overwhelmed. This was partly my fault for attempting to read them all at one time. It was too much. I had to make myself stop and read these poems over the course of a few days.

I want to be clear here: I'm not a professional critic. I'm an amateur editor/publisher, a hobbyist. I'm a writer, but mostly of personal essays and poetry. During Part III of Steady, I had to admit that I was out of my league. I don't feel qualified to evaluate these works as deeply as they deserve.

I thought I was reading a collection of personal poems, but I found myself in an almost epic work of literature. I'm not kidding or exaggerating. The pieces in Part III read like a series of art history lessons. I'm going to read them again. I look forward to reading them again. There's a lot to appreciate, and to learn.

The connection between these works and the other Parts of this collection are obvious. We are exploring the lives of women artists and writers from different eras and epochs. The struggles and obstacles these women faced, and overcame, are of a type, a pattern. Not identical, nor simplistically. But they all achieved levels of virtuosity and prowess that should be inspiring to anyone.

If reading these pieces was a bit tumultuous, the final poem in Part III provided a soft and beautiful return to nature, and more specifically, to the nature of art. Burnt Statues is an elegy of loss, but also of beauty and the purpose of art. It closes with a return to a homeland where "there is artistic blood in everyone."

Section IV - Blue, the final collection of poems is the briefest and contains a few of the shortest works of the volume, including Haiku, which works as a summation of all that we have experienced. I first wrote 'all that we have witnessed' but then I realized what Whitehouse had done to me. Reading the final poems here, I felt like I was coming home from an arduous journey. It was also like waking from a long and complicated dream.

In White Lilies, Whitehouse writes about her "summer of convalescence…"

When I woke, I remembered the dream.

I felt rejuvenated, no longer in pain,

all the parts of my body

relaxed and released, like a pond

turning over in springtime,

or a lily perfuming the air.

Death appears near the end, but it comes as a release, with "soft breezes, and all that flows through me is tinged with mystery." The seasons of spring and fall figure most prominently throughout Steady, but Whitehouse's final poem, Late Summer, Block Island, lands us in that season most full of life.

Steady is a truly massive accomplishment and a work that should be read more than once. Whitehouse isn't just telling stories with these poems. She's casting a spell and transforming all who are willing to surrender to it, bringing them on a journey of discovery, shock, wonder and finally, remembrance.

Steady is available from Dos Madre.